- Home

- Nana Ekvtimishvili

The Pear Field Page 5

The Pear Field Read online

Page 5

The school began to lose teachers as well. Only Tiniko, Dali, Vano and Gulnara are left from the old guard. Nowadays new teachers come, they teach a few lessons, realize the school has nothing to offer them and go again. New children have stopped arriving too. Maybe parents today are less willing to abandon their children or maybe there are better schools out there to abandon them in. Maybe idiots just aren’t being born any more.

That is why everyone is so surprised when one day the gates open and a well-dressed young woman in her thirties walks in with a girl aged about nine. The girl looks smart and well cared for but also nervous and guarded. Lela strokes the little girl’s hair, then walks them over to Tiniko’s office. Tiniko is expecting them. The woman explains that the little girl is related to her husband. Having lost her parents, she was being raised by her grandmother. Now that she too has died, the child’s relatives have decided to leave her with the school.

Tiniko shows them around with a large group of children in tow.

‘Do you like it here, Nona?’ the woman asks with a forced smile, looking down at the little girl. ‘Look what a big yard they have!’

‘The baths and showers are in here,’ says Tiniko, ‘and this is also where they do the laundry. The whole site belongs to us. The children spend plenty of time outside in the fresh air. Over there we have the dinner hall…’

‘You won’t be bored, will you? Look at all the nice children!’

The woman turns around to the children and gives them an exaggerated look of surprise, as if seeing them properly for the first time.

‘Oh, look! They’re so sweet!’ She goes up to Stella, who’s standing in the front row, cups her cheek and asks, ‘What’s your name?’

‘Stella!’ she answers happily.

‘Oh, you’re just delightful!’ says the woman, and strokes Stella’s cheek. Stella blushes shyly and gives a broad smile.

Lela can’t understand why the woman is planning to leave this pretty and apparently well-loved girl at the school.

‘We’ll come to see you every weekend. If we can’t come to you, you can come to us,’ the lady says, hugging Nona.

The girl looks embarrassed and wraps her arms around the woman hesitantly, as if she hasn’t known her for very long.

For the next few days Irakli is out of sorts. Nona, he realizes, is competition. Lela takes Nona under her wing. She moves one of the little ones to a different part of the girl’s dormitory and puts Nona’s bed in the prime spot by the windows. The other children are eager to see what Nona has in her little suitcase. She lets the other children look, while Lela keeps a watchful eye to make sure nobody takes anything. Stella is totally smitten with Nona, who gives her one of her dresses. From that moment on, Stella doesn’t run around dressed only in leggings; now she wears leggings and a pink, frilly jersey dress too.

*

It’s the afternoon. The children have had their lunch. Vano’s in charge today, which means everything should run smoothly.

It’s a bright, windy day and the children are playing football. A few of the children from next door have come to join in, which raises the stakes considerably. Irakli is fired up and playing so hard that he’s sweating heavily. Even the normally quiet Kolya is a completely different person when he’s playing football. He starts shouting and waving his arms around and, if a child from the school scores against the ‘normal’ kids, he throws himself on the ground and roars with happiness.

The match ends in victory for the ‘normal’ kids. The children disperse. Lela, who was refereeing, notices that Nona has gone.

‘Irakli,’ she says, ‘have you seen Nona?’

‘No,’ he replies, and runs off towards the drinking fountain.

‘Vano called her inside,’ says one of the others.

Lela heads quickly over to the school building and sees Vano coming out with Nona behind him. Vano is holding the class register and what looks like a textbook. Nona is holding a book too, clutching it to her chest.

‘You can keep that. Now go and play,’ Vano tells her, and walks down the steps. Nona just stands there looking dazed and disoriented, as if she doesn’t know where to go next.

Lela stares at Nona and sees she’s been crying. There are lines on her face where the tears have run down her grubby cheeks. Lela stops dead in her tracks, choked with rage, throat burning, heart pounding, and stares at Vano, who is already halfway across the yard on his way to the drinking fountain.

Lela stands rooted to the spot. Nona is still at the top of the steps, still clutching the book to her chest, still wearing the dress she had on when she arrived, although now it is ripped and dirty. Her once neatly plaited hair hangs loose and dishevelled.

‘There you go,’ Vaska says, walking up behind Lela. ‘The new kid’s right there.’

He sits down by the drinking fountain where Vano is still standing, thirstily gulping down water.

Nona starts walking gingerly down the steps. Lela stares at her, trying to interpret her expression, trying to place that look on her face. Nona doesn’t look much different from how she did before, except that now, like her dress, she seems damaged, soiled, tear-stained… Vano stops drinking and walks off.

Vaska watches him go, then sits down on the pavement. He wipes the sweat off his face with the hem of his T-shirt and shouts over to Nona, ‘Quick shag, was it?’ He laughs.

Nona doesn’t understand and carries on down the steps.

Without even thinking, Lela runs at Vaska, who is still sitting on the pavement, and kicks him hard in the face. Caught off guard, Vaska falls back onto the pavement. Lela kicks him again and again and Vaska can do nothing to defend himself.

The other children start running over from all directions. One shouts out in a panic, ‘She’s beating up Vaska! She’s beating up Vaska!’

Vaska struggles onto all fours and manages to get to his feet.

‘You bastard, what did you say?’ screams Lela, and punches Vaska in the chest. ‘What did you say, you little shit? Say it again!’

Vaska has blood pouring from his nose.

‘Nothing! What’s wrong with you?’

‘What’s wrong? I’ll fucking show you what’s wrong. Now tell me what you said!’

Vaska tries to get away.

‘What did he say? What did he say?’ ask the others.

Once again Lela launches herself at Vaska, who thinks it’s all over and is already wiping the blood from his nose with his T-shirt. A few of the children try to hold Lela back. She feels someone grab hold of her arm. Irakli, who only comes up to her shoulders, looks her straight in the eye and shouts, ‘Lela, stop it, now!’

She looks at Irakli in astonishment, although she doesn’t really know why. She stops and lets out a deep sigh. Vaska goes over to the drinking fountain and washes the blood off his face. The other children go with him, leaving Lela and Irakli standing there, alone.

A week later a relative from the village comes for Nona. She’s only a young woman but her face is deeply lined and weathered. Nona doesn’t know the woman but goes with her anyway. The woman shows Tiniko some documents, signs a few pieces of paper and takes Nona, her dirty dress and her little suitcase away from the school for ever.

Lela lets them out through the gates. Stella sits on the bench under the spruce trees and cries.

4

Lela dreams she’s taking Sergo round to use the phone, not Irakli. Sergo’s got Tiniko’s pink dress tucked under his arm. They walk up the stairs and Lela asks him who the hell he’s phoning anyway, given that he has no mother, given that he hasn’t got anyone. Sergo says nothing. He walks up to the door and rings the bell.

Mzia invites them in. She doesn’t seem at all surprised to see Lela with Sergo instead of Irakli. She leaves them in the hallway. Sergo lifts the receiver and dials, but it’s not a local number. Instead of six digits, this one has seven, eight, nine, more. The dial patiently clicks round and the number seems never to end… Lela asks where it is he’s calling, but Ser

go doesn’t reply, just dials and dials. Mzia’s daughter lies there in a ball on the floor, screwed up like a discarded cleaning cloth. Everyone’s pretending she’s not there. She moans softly, peeking out miserably like a poorly child from her sickbed. Lela notices that the girl’s beetle beauty spot has grown and spread to cover half her face. Suddenly Piruz, the local police inspector, emerges from the other room, deep in thought, with Mzia behind him. He walks over to the front door looking tired and troubled. Mzia opens the door. Piruz hesitates, then shrugs.

‘We don’t have that kind of thing here. Have they lost their minds?’ he says, and leaves.

Mzia closes the door and that’s when Lela notices the blood pouring out of a huge gash in the back of her head. Lela is terrified but doesn’t wake up, and suddenly she’s outside in the street with Sergo, and Irakli’s there too. They’re late; they hurry along and as they near the gates they see a crowd of locals and schoolchildren. There’s a bus at the side of the road. People are waiting. It looks like a funeral. Then Vano and Tiniko come through the gates. Tiniko is clutching Vano’s arm. She looks weak and unwell, barely able to drag her legs along. She moans softly and the hot summer breeze carries the sound to the sombre, now silent crowd. Lela suddenly realizes this is Tiniko’s funeral. She’s wearing that same pink dress Sergo had under his arm. The right side is covered in blood. Zaira’s there too, and Avto and Levan, and Vaska with that stupid smile. Levan comes over.

‘Tiniko’s been fucked so hard she can hardly walk!’

He laughs.

‘Go to hell,’ says Irakli.

It’s time to leave for the cemetery. Vano and Tiniko carry on towards the bus, slowly, like pallbearers carrying a coffin.

Zaira comes up to Tiniko.

‘And to think you said that dress didn’t suit you!’ she says cheerfully.

Tiniko doesn’t answer. She steps up onto the bus looking mournful.

The bus moves off. Lela spots Aksana standing in the rear window, smiling at her. She feels someone touch her on the shoulder. She turns around and sees Tiniko. Startled, she tries to tell her that she should be on the bus but the words stick in her throat, choking her. Tiniko starts squeezing her arm harder. ‘You see? Now we’re in trouble… And if the Board decides to inspect us…’ Tiniko tightens her grip and won’t let go, and Lela tries to shout, ‘Get off me!’ but the sound won’t leave her throat… She forces the words out in a hoarse rasp, followed by a feral roar which jolts her from her sleep.

She stands up, sweat-soaked, feels around for the bulb on the low ceiling and gives it a twist. She hears the metallic grind of the screw-thread and a flickering yellow light floods the gatehouse.

Lela sits on the bed for a few minutes. She’s wearing just a T-shirt and knickers. She pushes her fingers through her hair and takes a deep breath. The dream flashes through her mind. She can still feel the fear. She pulls on her trousers, feels around with her feet for her shoes and goes outside.

Lela sits on the bench under the spruce trees. She smokes a cigarette, gradually composing herself, and wonders whether a dream like that means she really is mad. She stares down at the bench, a plank wedged at each end into a deep slit sawn in a tree trunk. It’s the only bench in the yard and it’s been here for as long as anyone can remember. Both trees are living, growing, desperately trying to hold their half-sawn trunks together so that the soil’s nutrients can reach their upper branches; the plank anchors and links these two spruces, taken captive by man, held captive by each other, destined to live for evermore with a foreign body fused into their trunks.

Lela gets to her feet and starts pacing. The moon is shining daylight-bright in the yard. The school buildings are shrouded in darkness. There’s total silence; a few cars on the forecourt; the old Lada that’s been there for years, with no owner and no one to tow it away, abandoned, caked in bird droppings, falling apart. Lela stares at it for a while, until her attention is caught by headlights approaching fast down the road. She thinks of Sergo. In the distance she hears the light pat-pat-pat of a dog walking across asphalt and the sound a man makes heading home late at night.

Lela throws the butt away and goes back to her room. She unhooks a T-shirt from a nail on the wall, waves aside a cloud of gnats and carefully unscrews the red-hot bulb. Darkness envelops her. She lies down. Bit by bit her surroundings emerge and take shape: the door, window and table, the spruce branch outside, swaying in the breeze, and the shadow it casts, swaying in time. She drifts off into sleep.

Lela wakes the next morning to the sound of a child’s loud cries. Disoriented, she gets up, throws on some clothes and goes outside. The sun is already high in the sky. It must have rained in the night; the morning air feels pleasantly cold against her skin. There’s a large group of children standing by the gates, peering out to see who’s crying. Lela hurries over, shoves them to one side and sees a young woman standing just outside with a boy of around five, who is clutching her hand and sobbing loudly.

‘Shall I leave you here? Is that what you want?’ the woman asks him, yanking her hand around to try and shake him off.

‘Nooooo,’ wails the boy, clinging to his mother as best he can. He has large dark eyes and short, spiky hair. They live in the block next door and this isn’t the first time she’s brought her son up to the gates like this.

‘Have a good look! These children didn’t do what they were told either so their mummies and daddies brought them here!’ she says, pointing at the children peering wide-eyed through the gates at them.

‘Well? Are you going to do it again?’

‘No,’ he says tearfully.

‘Don’t be scared! We won’t eat you!’ Levan shouts.

The children laugh. Lela notices Vaska standing near Levan. His face is covered in purple bruises and he has a large black eye.

The little boy bursts into tears.

‘Well then? Shall I leave you here or take you home?’ She turns towards the children and shouts theatrically through the fence, ‘Children, where’s your teacher? I’ve got a new child for you!’

The boy cries even more loudly and clings to his mother’s legs. Trying not to laugh, the woman pats him affectionately.

‘There, there, it’s OK. I won’t leave you here this time. But only if you do what you’re told.’

‘I will,’ the boy says, his voice trembling.

They set off home.

*

The children disperse, most running over to the dinner hall, where Goderdzi will be holding his wedding reception the following day. Neighbourhood weddings and wakes are often held in the school. After all, who has room at home to host, feed and water five hundred guests? The children have all been invited and are over the moon; it’s rare for them to get the chance to play host.

The women from the flats next door are busy in the kitchens. They are not particularly close to Venera or Goderdzi but it’s tradition that when someone in the building dies the neighbours organize the wake and when someone gets married they organize the reception.

The women are making whatever they can in advance. They’ll prepare the hot food tomorrow. There’s a steady back-and-forth between the neighbouring flats and the school, but via the adjoining courtyards rather than through the main gates. Avto has widened the gap in the fence so that the women can squeeze through with their dishes and bowls without catching their clothes on the wire. They make their way across the playground and down the path alongside the pear field before coming out by the dinner hall, where they find a large group of children milling around, desperate to be given jobs to do.

Lela is in the dinner hall, lifting the large pots down from the shelves. Meanwhile, Koba and the other boys are bringing in boxes of rented crockery. Irakli walks ahead, clearing a path.

‘Hey, Lela,’ says Irakli. ‘Can you come outside for a sec?’

Lela hurries after him along the path that borders the pear field.

‘Hurry up!’ he says, and points up the path at Mzia, who’s popping hom

e to fetch her walnut-grinder.

‘Mzia’s going home to get something,’ he says, racing ahead. ‘She might let us use the phone…’

‘Are you soft in the head?’ Lela snaps. ‘You can’t call her, can you, because she’s gone to Greece, you idiot.’

‘I’m gonna ring Ivlita. She might have a number for Mum. And if not… well, then I won’t call.’

Irakli navigates the gap in the fence. He looks back to see Lela still standing in the school grounds staring at him.

‘What do you need me for, then? Go and ring her!’

She turns and starts heading back.

‘Lela, please!’ Irakli calls.

She turns back and looks at Irakli through the gap in the fence. In the distance she sees Mzia striding up into the tower block.

‘Just one more time, Lela. I’ll never ask you again, I swear!’

Lela looks at Irakli’s big ears and ardent expression and can’t help but laugh.

‘You’d better not,’ she says, and steps through the fence.

They find Mzia on the landing. She shows them inside, brings out the small stool and disappears into the kitchen.

Irakli calls Ivlita and asks for a number for his mother in Greece. Lela asks Mzia for a pen and paper, then writes down the number as Irakli reads it out.

Irakli says goodbye, hangs up and stares at the piece of paper for a while.

‘Read it for me,’ he says with determination.

Lela reads out the number.

Irakli dials. The phone on the other end rings, then Lela hears a familiar voice.

‘Mum, it’s me,’ says Irakli weakly.

‘Irakli!’ she says, sounding pleased but surprised. ‘How are you? I still haven’t made it home, have I? Things have been so crazy… I’ve been so busy, so much to do… and I didn’t have the money to come… But I’m about to start work and then I’ll have enough to come home. I should send you some presents, shouldn’t I…’

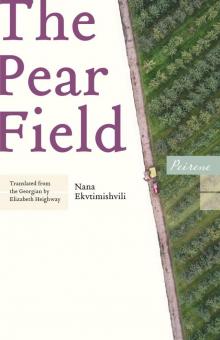

The Pear Field

The Pear Field