- Home

- Nana Ekvtimishvili

The Pear Field Page 10

The Pear Field Read online

Page 10

‘Is that their car?’ she asks.

‘I don’t know,’ Madonna says dismissively, and pulls out another photo. This one shows the rest of John and Deborah’s family, adult children who, according to Madonna, already have their own homes. The next few photos are of other children John and Deborah have raised, and who look like neither their parents nor each other. The first few are white and fair-haired, but then comes a photo of a young black man wearing a black gown and a strange-looking hat, looking directly into the camera and flashing a broad toothy grin. The children burst out laughing.

‘Jesus Christ!’ exclaims Levan.

The children are in hysterics. Madonna tries to explain what’s happening in the photograph but nobody can hear her above the din. Lela catches enough to work out that this is John and Deborah’s adopted son on his high school graduation day.

I bet he got a gold medal too, thinks Lela, remembering Kirile.

Koba and Lela meet at the bottom of Kerch Street. Koba doesn’t want anyone to see him with a girl from the School for Idiots. He takes back roads the whole way there and he tells her to duck down when they see someone he knows.

The sun has been beating down all day but when Koba drives out of the city a cool breeze rushes in and cuts through the heat of the car.

Lying there with her legs open, Lela hears the crickets chirping and thinks that maybe somebody’s coming. She props herself up on her elbows while Koba looks around until he’s satisfied nobody’s there. Lela lies back down, wraps her legs around Koba and moves with his rhythm. Koba tries to take control. Almost instinctively Lela grabs one of Koba’s skinny buttocks and pulls him into her, harder, and feels that warmth in her stomach, and her entire body as one, a bundle of fibres, a balloon full of water sloshing gently back and forth, back and forth, until the warmth floods out of her stomach and through her whole body, and she grips his buttock hard and lets out a sudden cry. Deeply aroused, Koba stares down at her, a drop of sweat hanging off the end of his nose, then surrenders to the ecstasy and comes.

Lela gets out of the car and goes into the field to pee. She doesn’t hurry back. Returning to the car, she finds Koba dressed, standing by the driver’s door, smoking. Lela asks for a cigarette.

They sit in the car in silence. Koba takes a five-lari note out of his jean pocket and hands it to Lela.

‘I don’t want it,’ she says briskly.

Koba looks at her in surprise.

‘I don’t want it,’ she repeats.

Her face is flushed and her hair, wet with sweat, hangs down over her forehead. Koba sees a hint of a smile on her face.

‘I came too, didn’t I?’

Koba slaps Lela across the face with the back of his hand and splits her lip. She cries out in pain and covers her face with her hand.

‘You’re not right in the head, you know that? Get out of the car!’

Lela opens the door with one hand, the other one still pressed over her mouth, and gets out. Koba throws the five-lari note at her and slams the door. He backs out of the field, leaving Lela standing there on the dirt track surrounded by corn.

The sound of the car fades. Lela picks up the five-lari note and shoves it into her pocket. The crickets are chirping more loudly now. It’s dusk and the entire landscape has a bluish hue. A light breeze dances across the field and Lela can hear the sound of the sea in the rustling corn. She picks up her pace. Back at the road, she waits to flag down a car.

After a short time a white Lada 4x4 stops for her. The driver is a man with a tired face and labourer’s hands. He looks at Lela’s bloodstained mouth.

‘What happened? Did someone do this to you?’

Lela starts crying in spite of herself. She wipes her dirty hands across her cheeks, rubs her eyes and screws up her face. She feels something lodge in her throat, choking her.

The man pulls over. He offers her a bottle of water.

‘Hold out your hands for me and you can give your face a wash.’

Lela gets out and cups her hands. She splashes the water onto her face.

‘A young girl like you shouldn’t be out here alone,’ the man says, when they’re back in the car and heading down the road to Tbilisi. ‘There are all sorts of bad people about… Are your parents still around?’

‘Yes,’ replies Lela.

‘How old are you?’

‘Eighteen.’

‘Where do you live? I’ll take you home.’

‘Keep driving and I’ll tell you the way.’

‘What were you doing out here anyway?’ asks the man.

A large lorry thunders past them with a deafening rumble, spewing thick black smoke.

‘A friend took me for a drive,’ Lela says. ‘And then he drove off and left me there.’

‘And did your friend do that too?’ asks the man, without looking round. Lela glances at the man and is surprised to see deep, broken furrows running out from the corner of his eye to his temple.

He shakes his head.

Lela looks out of the window. The man’s questions are making her tense.

By the time they drive into the city the light is fading fast. Lela recognizes her street, but sends the driver a different way and asks him to stop in front of a block of flats.

‘Anywhere here will do. Thank you,’ she says.

The man peers into the yard. There are children playing and a few young men hanging around. It’s just an ordinary yard lit by the setting sun, with leafy shadows that embellish the tower block walls and a mother calling for her child from a top-floor window.

‘Stop going off with people like that. There are too many weirdos out there,’ says the man.

Lela gets out of the car and runs into the building that’s not really hers.

*

Later that night, as Lela stands in the wash block, she is suddenly unnerved by the sound of gushing water echoing through the dark, deserted building.

She goes into the gatehouse. Through the darkness she can make out Irakli lying on her bed in a deep sleep. She gazes down at him. The moonlight is streaming onto his face. The Americans were right. His face is soft, his skin pale and almost translucent. He is breathing heavily. Lela sits down on the bed and takes off her shoes. She uses her back to shunt Irakli towards the wall. He squirms, then goes back to sleep. Lela can feel him breathing through her back. She remembers Koba, the five-lari note in her trouser pocket and the man with the deep creases round his eyes. She tries to think, but the thoughts fail to form in her head and soon Lela too is asleep.

The next day Lela goes round to the tower block next door. The yard is usually empty at this time of year: it’s the summer holidays. The few children left behind sit at the table in the shade, playing cards and looking miserable. A group of young men including Koba and Goderdzi, who is getting ready for his second wedding, are hanging around nearby. This time Goderdzi isn’t under his car; today they’re watching Gocha wash his car with a hose. Lela goes over to the men and stands right in front of Koba. Koba is taken aback. The other men look on in astonishment. Lela pulls the five-lari note from her pocket and holds it out to Koba, who turns bright red.

‘Here, you can take your five lari – I don’t want it!’ she says.

‘Get lost, will you?’ Koba hisses, raising his hand angrily and turning his back, before turning to face her again and muttering, ‘Just piss off!’

The men laugh.

‘What’s going on? What does she want?’ Gocha asks.

‘Give it to me, love, if you don’t want it,’ sniggers one of the others.

‘Give it to your grandmother and go fuck her instead,’ says Lela, throwing the money at Koba’s feet.

The others burst out laughing. Someone starts clapping. A man with a goatee snorts and says, ‘Nice one!’

‘You kept this quiet, Koba!’ says a man in a denim waistcoat. ‘God, you must have been desperate!’

‘Come here, you bitch! You’re fucking dead!’ Koba shouts, and lunges at Lela. The other me

n hold him back as Lela starts walking away.

‘Fucking nutjob!’ shouts Koba.

Lela spins round.

‘Don’t you ever let me see that pile of rust in my yard again or I’ll tell Tiniko about your five lari, and Piruz too, and then you’re fucked, aren’t you? Well and truly fucked by some nutjob, just like you wanted! So take your five lari and buy yourself something nice,’ she spits, ‘like your mother!’

‘Steady on, love,’ says a man with a smooth, deep voice. The other men hold Koba back. Gocha tries to turn the hose on Lela but the jet doesn’t reach her. The guy in the waistcoat picks up a pebble and throws it hard at Lela’s ankles.

‘Leave her alone, man, she’s a girl,’ says the deep-voiced man.

An old man is looking out of one of the windows. Then a woman sticks her head out of another and asks angrily what’s going on.

‘Nothing, Mum. Go back in,’ says the man with the goatee.

One evening when the light is fading, Koba bumps into Lela at the end of Kerch Street and punches her in the face. Lela falls to the ground and Koba kicks her repeatedly in the stomach and back. After that, he walks off and disappears from her life for ever.

8

August arrives. Time always passes slowly at the school, but now it seems to have stopped completely. The streets are empty; the air is still; even the dogs do as little as possible, shifting only to follow the creeping shade. There is no prospect of rain. There are no cool spells. Going outside is almost impossible. The sun blazes down from the moment it comes up, an enormous glowing ember mercilessly searing this side of the world. The ground is bone-dry, cracked like the top of a cake, and even the rust-coloured ants seem desperate, running frenetically across the scorching earth, looking for a crevice to shelter in and cool their tiny burnt feet.

In the evening when the sun goes down, the air still sits heavy. The moon casts shadows that transform the landscape. At last a hesitant breeze wafts in and the branches begin their gentle sway. The crickets chirp.

The children stagger around giddily in the heat. They don’t want to play football. They don’t want to eat. For some reason no one can fathom, Dali stops them playing with water to cool off. When nobody’s looking, a few of them still manage to fill bottles with water and pour it all over their heads.

*

One evening when Dali and the children are hiding from the heat in the yard’s shade, Father Yakob arrives wearing his black cassock and veil. Tariel’s son, Gubaz, has taken a turn for the worse.

‘I thought he usually got ill in the spring,’ says Dali pensively.

‘We’ve done everything we can. The doctor’s been out too. It’s up to God now,’ says Father Yakob gravely. ‘They even had Piruz round, but what on earth can he do? You can’t throw someone in jail for being mentally ill.’

Piruz appears looking tired and anguished. Gubaz, he says, had chased his own parents round their vegetable garden with a hatchet.

‘Thank goodness Kukura was there. He managed to catch him somehow and tied him up,’ says Piruz. ‘He took a couple of punches to the head, though… That’s some right hook Gubaz has, uffff…’ Piruz shakes his head. ‘He can’t go on like this. The boy needs medicine! He’s OK one minute, like this the next… His parents had a lucky escape this time.’

‘You’re right,’ Dali agrees. ‘He’s had bad spells before, but nothing like this. One time he started telling everyone he was God and walking around with eggs in his pockets. A few days later – right as rain…’

‘You never know when it’s coming. If only he was just feeble-minded like the little ones you have here,’ says Piruz, wiping his forehead with a crumpled handkerchief.

‘There’s something else at play,’ says Father Yakob. ‘The Evil One spotted his weakness. He only needs the tiniest whisper of invitation. He knocks at your door and if you open it even an inch he comes right in and takes possession!’

‘The Devil, Father?’ Piruz asks, turning pale.

‘Don’t let his name pass your lips! Lord have mercy!’ says the priest, making the sign of the cross. The others cross themselves too, three times.

‘What is the cure, Father?’ asks Dali anxiously.

‘Prayer. Fasting. Vigilance. The Church and God’s assistance,’ he proclaims.

‘Good Lord,’ says Dali, as if she thinks this almost impossible.

‘If curing madness were that simple there wouldn’t be so many lunatics walking around,’ says Avto, who has just come over. Avto gives Piruz and Vano brisk handshakes, then Father Yakob too. Clearly expecting a kiss on the hand, the priest narrows his eyes in disdain as Avto returns to his blue van.

Lela goes to open the gates. Piruz finishes his cigarette and heads off too.

Father Yakob frowns suddenly and looks at Dali.

‘Do these children know how to pray?’ he asks.

Taken aback, Dali seems unsure how to answer. The children stare at their feet awkwardly, embarrassed to be found wanting by a man of God.

‘Teach them their prayers,’ says Father Yakob sternly. He slips his hand into the pocket of the enormous canvas waistcoat he’s wearing over his cassock and pulls out a couple of pamphlets. He hands one to Dali. ‘Bedtime prayers. Make sure you teach them – you are their godmother, after all.’

Dali, red-faced, bows meekly, kisses Father Yakob’s hand and takes the pamphlet.

One evening Lela wonders if bedtime prayers might have some merit after all, if they might chase away her strange, dreadful dreams. She finds Dali watching TV with the children.

‘Dali, what did you do with that leaflet the priest gave you?’

Dali drags herself out of the armchair, goes over to a tatty shelf and pulls out the pamphlet.

‘To be honest, I can’t read it,’ she says, flicking through the pages. ‘I can’t make any sense of formal prayers like this.’

Dali sits down in the armchair. Lela calls the children over. Dali pushes her glasses up her nose, stares down at the page for a while, then shuts the pamphlet and sets it aside. She looks at Pako and Stella, who are sitting right next to her.

‘I was your age when my mother died,’ she begins.

‘Did you grow up in a school for slow children too?’ Levan asks cheerfully. The children laugh, but Dali carries on.

‘No, my grandmother raised me, God rest her soul.’

She looks up at the cobweb-covered ceiling and makes the sign of the cross. The children cross themselves earnestly too. Some kiss the crosses around their necks, as they have seen others do.

‘I didn’t know the first thing about praying or going to church – I grew up in the village. We did have a church, if you can call it that, up at the top of the hill, but it was so old… The roof had fallen in and there were trees growing inside the building. Just walls and a couple of icons really. My mother was so young when she had me. She was only twenty-one when she died. They used to take me there to light candles under the icons. At night my mum would put me to bed and say a little prayer. A children’s prayer, though – a rhyme. After she died I’d say it with my grandmother instead. Even now, before I close my eyes, I say this prayer and I have no fear, for God is with me.’

The children hang on Dali’s every word. Dali exhales deeply, then begins to recite:

‘Now I lay me down to sleep,

I pray the Lord my soul to keep…’

When she comes to the end she wipes a tear from her eye. Vaska looks on from the doorway, a smile of slight disdain on his face.

All of a sudden, a strong breeze rushes in through the window and the heavens open. The children, jubilant, run to the window and thrust their hands into the cooling rain that spreads like a salve across the heat-scorched earth. The smell of wet asphalt fills the air.

‘Ika, do they have rain in America?’ asks Stella, trying to squeeze herself under Irakli’s arm as he leans on the windowsill.

‘Yeah, rain and hail. And storms. Haven’t you seen their storms on TV? They have tor

nadoes so big they’ll carry your whole house away!’

‘Ika, no!’ says Stella, covering her mouth with her hand. ‘In that case don’t go!’

That night Lela dreams she’s back at the edge of the pear field. The children are playing football behind her. Lela runs out onto the field to fetch the ball but after a few steps she finds herself sinking into the soft, waterlogged earth. Suddenly the earth drags her in up to the waist. She reaches out to grab onto the gnarled roots. She tries to shout to the children but they’re nowhere to be seen. She sinks deeper and deeper into the field.

The next morning Lela gets up early to let a few cars out, then goes to the dinner hall.

She doesn’t like seeing the hall empty of children. The morning light is streaming through the windows and, where the dusty sunbeams fall, Lela can see bits of leftover bread on tables still not cleared from the night before, and glasses covered in fingerprints.

She goes to the cupboard and finds a piece of bread, spreads it with plum jam and eats it on her way out into the yard. None of the teachers are in yet and the children are all still asleep. A single hungry dog wanders through the spruce trees.

Tiniko arrives at work. Lela opens the gates and Tiniko click-clacks unsteadily across the yard in her wedge heels. Lela closes the gates behind her.

‘Tiniko,’ she says casually, ‘I can’t give you the parking money this month.’

Tiniko sits on the plank under the trees and pulls off her shoe to remove a stone. She frowns at Lela.

‘Why not? Have you spent it?’

‘I had to pay for a lot of things. For Irakli. I’ll pay you next month.’

Tiniko says nothing. She squeezes her swollen foot back into her shoe and stands up.

‘Tell me he’s learning something at least,’ she says.

‘Yeah, he’s learning,’ Lela replies with a shrug.

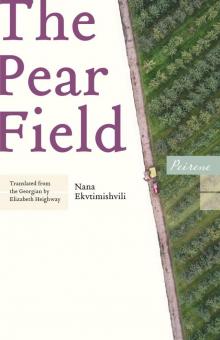

The Pear Field

The Pear Field